Climate Policy Initiative: The challenges of tackling climate change in the rich and middle-income countries including Pakistan, East Africa, and South Africa — a report by the UN Environment Programme

The Climate Policy Initiative has a director who says the rich countries face a challenge in coming up with money to keep developing nations on board with efforts to cut global emissions.

The impact from global warming on the world’s lowest income countries has been particularly harsh and they are not responsible for much of the greenhouse gasses that are causing the rise in temperatures. Flooding in Pakistan this summer that killed at least 1500 people and a multi-year drought in East Africa are evidence of “mounting and ever-increasing climate risks,” the UN report says.

Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environment Programme, stated in the introduction to the report that political will is needed to increase adaptation investments and outcomes.

She said we need to get ahead of the game if we don’t want to be spending the coming decades in emergency response mode.

The UN published the report days before the climate conference starts. In a separate report published last week, the UN said the world isn’t cutting greenhouse gas emissions nearly enough to avoid potentially catastrophic sea level rise and other global dangers.

The world has known for a long time that it has to hold the line at 1.5 degree Celsius to stave off the worst effects of warming. We have to cut carbon emissions by at least 42% from this year’s levels. That’s been the aim since 2015, when world leaders came together to sign the Paris Agreement. At the Conference of Parties meeting in COP26, global climate negotiators came with a clear mandate. They left Glasgow with the carbon equation far from being solved at the end of the negotiations.

“The discourse needs to be raised significantly, the level of ambition, so that you can actually continue to do what you’re doing on mitigation even more, but you at the same time meet the adaptation needs,” says Mafalda Duarte, CEO of Climate Investment Funds, which works with development banks like the World Bank to provide funding to developing countries on favorable terms.

Yet most of the financing that’s being doled out is going to projects like wind and solar farms that are aimed at limiting further increases in global temperatures. That’s left a huge shortfall for projects like building flood defenses, or introducing drought-resistant crops that can help poorer nations cope with warming that’s already happened.

Now, rampant inflation and an energy crisis caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine could complicate efforts to convince developed nations to make good on their financial commitments. That’s to say nothing of the need to boost future obligations in line with the trillions of dollars that developing countries will actually need to prepare for a hotter Earth.

“We have to change our mindset and the way we think, because, actually, when it comes to climate, you know, an investment across borders in other places is a domestic investment,” Duarte says.

Climate Change and the COPs: What’s the fuss? The buzz at the climate conference 2013 London, September 23-27, 2015

The debate is raging at the conference. Climate activist, who was a media sensation at the last year’s conference, said during an event in London this week, “The COPs are not really working.” The COPs are used by people in power to get attention with a variety of different kinds of greenwashing.

The activists believe that glaciers are melting faster than the countries can come to an agreement on policies to limit climate change. The landmark Paris Agreement adopted in 2015, was the most significant decision yet to come out of one of these conferences. That agreement is a foundation for many efforts today to take action on climate change. The research supported limit on how much global warming countries are willing to tolerate makes them accountable and encourages them to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C above industrial levels.

The world has warmed by 1.2 degrees Celsius so we are out of wiggle room. The net-zero greenhouse gas emissions need to be achieved over the next few decades. It has a short time to transition the entire world to clean energy. If we do not act, then we will reach a whole new degree of climate destruction, including wiping out the world’s coral reefs and turning many of the world’s mega cities into “heat-stressed” places.

The money is supposed to go toward new and improved infrastructure that might help keep people safe in a warming world. That could mean that the cities are designed to be better at beating the heat or less likely to be wiped out in a wildfire. It might mean expanding early warning systems that alert people of a flood or storm. At a time when the costs of adaptation are projected to hit $300 billion a year by the end of the decade, there is a push this year to get even more funding for these types of projects. Advocates are also pushing for more locally led solutions since what it means to live with climate change looks different from place to place and the people most affected by climate disasters haven’t always been included at planning tables.

There’s also growing outrage this year about the lack of support for communities that have already suffered irreparable damage from climate disasters. Small island nations, for instance, have already had to evacuate entire populations from disappearing islands. Even though they have not made a significant contribution to the pollution causing climate change they have had to shoulder the costs.

The concept of reimbursement is not aid, but is based on the principle of pollution pays, according to the editor of Down to Earth in New Delhi. This financing “must be on the table — not to be pushed away with another puny promise of a fund that never materializes”, Narain writes in the 1–15 November issue.

There have been some bright spots. By the year 2020, Australia will reduce its planned cut to 43 percent below 2005 levels, thanks to a newly progressive government. A handful of other countries, including Chile, which is working to enshrine the rights of nature into its constitution, have already promised more cuts or say they will soon. Smaller polluters like Australia are trying to catch up after submitting goals that were poorly written or lacking in detail. “A lot of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked,” Jansen says.

Other wins have simply put emitters on the path to making good on last year’s promises. Fransen points to the United States, where the recent Inflation Reduction Act represented a massive step toward meeting its pledge of a 50 percent emissions reduction from 2005 levels. But the US still isn’t on track to reach that commitment. She says that by increasing the ante this year it would make it difficult for the nation to be heard.

Fransen is one of the people in the business of keeping track of all those emissions plans and whether countries are sticking to them. It is difficult to take stock. It means measuring how much carbon nations emit. The greenhouse gas emissions will have a large impact on the climate over the next 10, 20, or 100 years.

Unfortunately, it isn’t easy to determine how much CO2 humanity is producing—or to prove that nations are holding to their pledges. That’s because the gas is all over the atmosphere, muddying the origin of each signal. Carbon is released by natural processes like decaying vegetation and thawing permafrost. Think of it like trying to find a water leak in a swimming pool. Researchers have tried pointing satellites at the Earth to track CO2 emissions, but “if you see CO2 from space, it is not always guaranteed that it came from the nearest human emissions,” says Gavin McCormick, cofounder of Climate Trace, which tracks greenhouse gas emissions. That is why we need more advanced methods. Climate trace can train its models to use steam from power plants as a proxy for emissions. Some scientists are using weather stations to get a better idea of how much pollution they are creating.

COVID-19: Anopheles stephensi vs. Dire Dawa in Ethiopia and what to look out for at COP 27

More than one million lives might have been saved by distributing COVID-19 vaccines more fairly according to models. How to decarbonize the military and what to look out for at COP 27 are some of the topics covered.

• Much of the focus will be on evaluation, assessment and accountability. “We can’t just move on to new commitments without getting a grip on whether the current commitments are being carried out,” says climate-policy analyst David Waskow.

Insecticide-resistant mosquitoes have made their way from Asia to Africa, threatening progress there towards eradicating malaria. In a study in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia — the site of a malaria outbreak — Anopheles stephensi accounted for almost all adult mosquitos found near the homes of participants with the disease. The notorious species can breed in urban environments and persist through dry seasons. It could infect more than 100 million people in Africa if they are not protected by vaccines and other control measures. Fitsum Tadesse says there’s no silver bullet for this fast-spreading mosquito.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03572-0

What are the COP27 Climate Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerabilities? A UN report on loss-and-damage of the Middle East and Africa

The US armed forces put out more CO2 than any nation in the world. Most militaries are spared from emissions reporting. A group of researchers outline how to hold the military to account.

It is possible to leave out one billion people from a data-driven plan for the world. “That’s the troubling truth behind net-zero emissions proposals.” She argues that we can’t we can’t engage meaningfully with the concept of net zero — at COP27 and in general — without Africa-specific data, appropriate models and African expertise.

Oliver Mller got some valuable lessons after he left his job as a Google astronomer. It is important to not be a hero. You are putting your mental health and physical health at risk if a task is not finished with the least amount of risk.

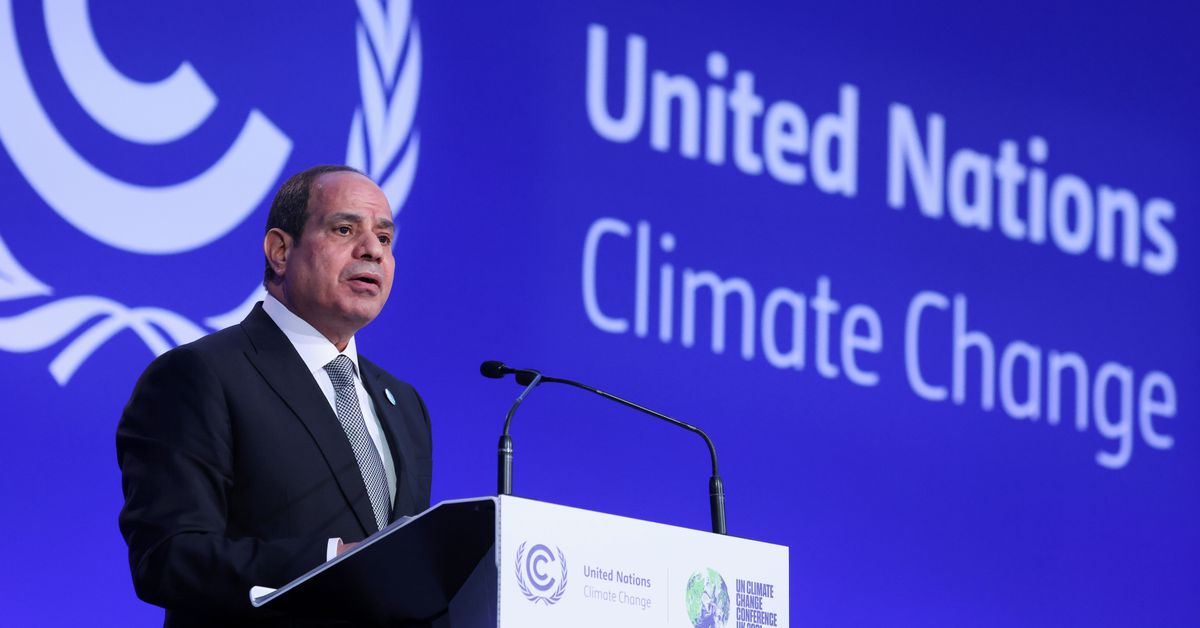

The leaders of wealthy nations were warned by the Egyptian hosts of the COP 27 climate conference that there can’t be a backsliding of commitments made at the COP26 in Glasgow, UK.

The president of the Egyptian Academy of Scientific Research and Technology in Cairo says that scientists from climate-vulnerable countries will be asking for more funding for research. Countries, he says, need to conduct more of their own climate studies — especially in the Middle East and North Africa, which already experience low rainfall and arid conditions. The Arab world accounts for just 1.2% of published climate studies, according to an analysis1 published at the end of 2019.

In 2015, Egypt estimated that it needs to set aside $73 billion for projects to help the country mitigate climate change and adapt its infrastructure. This number has tripled to $246 billion according to the environment minister. “Most climate actions we have implemented have been from the national budget, which adds more burden and competes with our basic needs that have to be fulfilled.”

However, the LMIC cause was boosted when the phrase “losses and damages” featured in the latest report on climate impacts, adaptation and vulnerability from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published in February. The report’s chapter on climate impacts in Africa is led by Christopher Trisos, an environmental scientist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

Ian Mitchell, a researcher at the Center for Global Development in London, warns that agreement on loss and damage could become a deal-breaker at the meeting. Loss-and-damage finance will not be new money for high-income countries if they agree to the principle and accept it as part of their aid spending.

The politics will probably get messy and it is not likely that these issues will be resolved in Egypt. He adds that loss-and-damage finance can no longer be avoided by the high-income countries, especially given that climate impacts in vulnerable countries are becoming much more visible and severe.

The organizing of this year’s COP in Africa has changed according to Fouad. “We are expecting more attention towards issues that are crucial and meaningful to us Africans and relevant to most developing countries, such as food security, desertification, natural disasters and water scarcity. This COP is a chance for more African youth, non-governmental and civil-society organizations to be heard.”

“The challenge is going to be, how do we maintain momentum when there are so many short-term crises and pressures, and yet the climate crisis is intensifying?” says Amar Bhattacharya, who is part of an independent group of experts that was convened ahead of COP27 to advise conference leaders on how to increase climate financing.

The Impact of Climate Change on Developing Countries: The Barbados Prime Minister’s Challenge and the U.S.’s Special Advisor to Climate Change

Developing countries received an estimated $83 billion from private and public sources in 2020, according to a recent tally by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The bulk of the money is being delivered through loans, which critics say add to the debt burden of governments that are already on shaky financial footing.

Mia Amor Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, has said developing nations should at least have access to loans on the same favorable terms that were offered to their counterparts in the developed world.

“We have incurred debts for COVID, we have incurred debts for climate, and we have incurred debts now in order to fight this difficult moment with the inflationary crisis and with the absence of certainty of supply of goods,” Mottley said at the United Nations in September. “Why, therefore, must the developing world now seek to find money within seven to 10 years when others had the benefit of longer tenors to repay their money?”

There are calls to provide more climate financing in the form of grants that don’t need to be repaid, according to a person who works at the World Resources Institute.

Some impacts from climate change are irreversible, according to the UN, and even if countries could immediately stop emitting greenhouse gasses, the effects of global warming would still be felt for decades.

It can be hard for vulnerable countries to get funding. Data is required for the process to be shown how climate funding would be used and how it would benefit the climate.

For the past year, United States President Joe Biden has been pushing to quadruple U.S. climate funding for developing countries to more than $11 billion annually starting in 2024. About half of that money needs to be appropriated by Congress.

John Kerry, the United States’ special presidential envoy for climate change, has suggested that the president’s goal could be at risk depending on the outcome of midterm elections in the U.S.

Kerry said in October at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington, DC, that developed countries need to make good on their finance goals.

But observers say those goals are just a drop in the bucket. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, has said emerging economies will need at least $1 trillion a year to eliminate or offset their carbon emissions.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2022/11/06/1133532209/money-will-likely-be-the-central-tension-in-the-u-n-s-cop27-climate-negotiations

Changing the paradigm of action: How to become more effective in changing the world, rather than just talking about what you can do, instead of what you want to do

A way to raise ambition is centered around real results, rather than the rhetoric of $100 billion, says Bhattacharya.